One of the earliest ponderables we’re asked to consider concerns issues of observation and perception. Does a tree falling in the woods make a sound when no one’s around?

A 21st century media variant runs like so: If an event takes place and no one shares it, did it really take place at all?

Consider China, where tensions between pro-democracy protestors in Hong Kong and the Chinese government continue to rise. Just this week masked assailants attacked protestors and police fired rubber bullets at them.

That’s what we see and hear on the outside. Inside China, the story is different. There, the country’s propaganda and censorship apparatus works to shape narratives and keep information from the public. The result is that not much is known in the country about why protests are taking place, only that they’re an affront to China and its One Country, Two Systems policy.

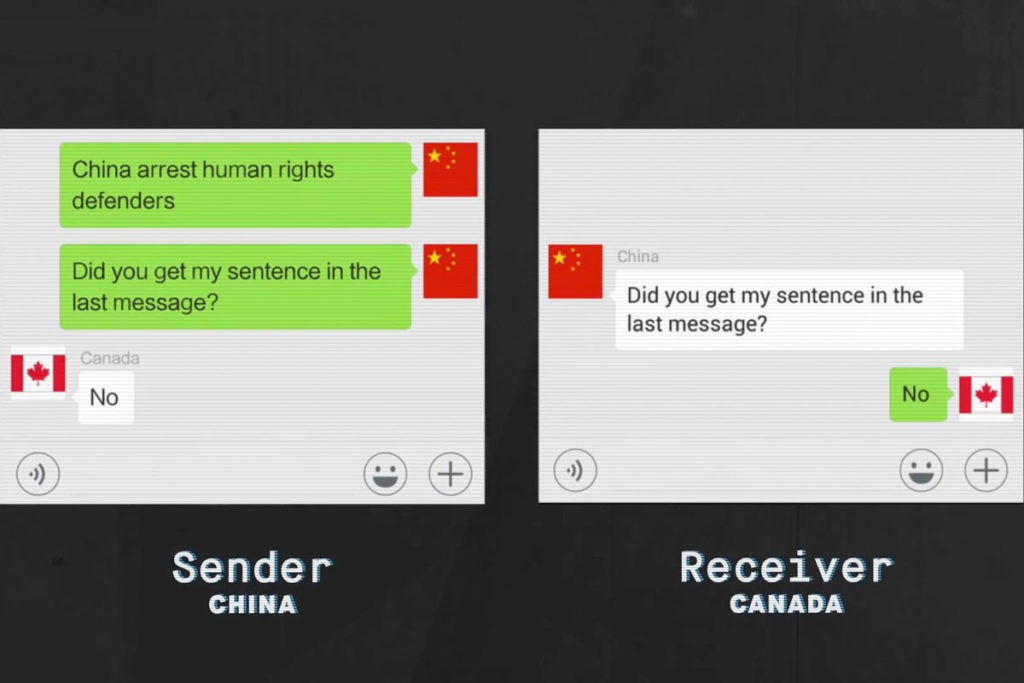

Quartz recently published a video demonstrating how the Chinese actively bury news coming out of Hong Kong. It’s a fascinating look at the country’s censorship technology. It includes removing social media posts containing specific words and phrases (common and well known); removing single messages (be it a video, image or text) from within people’s private message threads (less well known and eyebrow raising); and flooding the information field with counter-narratives (a common propaganda tactic).

The attempt is full state control of the information ecosystem. It begins with disappearing content, continues at scale with state narratives, and continues by gaslighting those who say a story or event runs differently.

Take the state-run China Daily newspaper. Visit its web site and the stories about Hong Kong are few. Those you do find call the non-violent protestors “radical rioters” who must be “smacked down“. A far cry from what the rest of the world has seen and watched in international coverage.

China’s official channels decontextualize the protests. Mainland Chinese watching the country’s most popular news program aren’t told why there are protesters, only that there are protesters, and no matter what the protests might be about, a silent majority supports China’s Hong Kong policies.

Aside from this, the protests don’t really register as news. One of the few Hong Kong-related items on the China Daily home page is a special advertorial on doing business in Hong Kong.

Combine the non-coverage with the country’s ability to disappear social media posts about the protests and, arguably more sinister, its ability to silently block individual messages within chats between individuals and you see how effective traditional propaganda becomes when combined with cutting edge digital censorship.

Into the information vacuum go the words, images and narratives of the state. A 2017 study estimates that the Chinese government fabricates about 448 million social posts and comments each year.

If mainland Chinese can’t see the protests, don’t hear about the protests and can’t share information about the protests, what does it mean to say that that they’re taking place?

Primary in the activist’s toolkit is that someone, somewhere bears witness and passes information to a larger collective that can then take action based on that information. What happens when the ability to do so is silently stripped away?

What we see in China are the early years of a state’s attempt to digitally root out that capability. More, we’re watching the attempt to do it surgically and at scale.

Some of the techniques might seem blunt or crude at this time but it’s a given that they’ll only improve moving forward. That other authoritarian states are watching, learning and looking to get their hands on the technologies and methodologies to do the same is also a given.

Give it a generation. As the tools grow more subtle and difficult to perceive, the state’s ability to simulate reality and codify opinion will grow more complete. Reality won’t be televised. Instead, and unfortunately, it will be delivered by bots and trolls, fakes deep and shallow. With it, the state’s will have an ever growing capability to gaslight and silence those that disagree.

We’re watching how this new censorship tech works in Hong Kong, one protest at a time.

Featured image – Detail, Fables and Fairy Tales by Filip Zrnsević.