For a long time now I’ve skipped ahead when John Coltrane’s Giant Steps comes on. Scandale, you say? Not really. I’ve heard the song so many times it’s internalized. Skipping it is pretty instinctual.

I do the same with most any tune I once loved and then listened to too much. Sometimes I’ll even skip a song I currently love in an attempt to save it for future listening. I know if I listen now I won’t appreciate it as much later. If I over-listen, I’ll be bored when I really want to listen. Songs become mundane.

Language suggests something more violent. We kill things by loving them too much. I listened to a song to death.

Music brings joy. Much of it through elements of surprise. This could be a melodic, harmonic or rhythmic change or something else altogether unexpected… until, that is, you’ve listened to and internalized the song to such a degree that what previously delighted becomes pedestrian. The release relieving a song’s tension no longer releases. Instead, it fizzles. The funk stops being so funky.

This happened to me long ago with Giant Steps. It doesn’t make me appreciate the song less. I still know the song is a seminal work. There’s no denying it. Here’s a wonderful breakdown of why courtesy of Vox Earworm.

A Song’s Half Life

Greatness aside, songs have a certain half life beyond which they become uneventful. Basically, they become too known. The better the song, the longer it takes to happen but it happens nonetheless.1 So, last summer’s quick hit peters out by about August. Songs like Giant Steps after a number of years. Even in its greatness – or, perhaps, because of its greatness – a song eventually becomes a monument. Awesome, sure. But static, stuck in a place, a time, a no longer present feeling.

Until you can hear it anew.

Which is what happened to me when Camille Bertault’s poppy, vocalese cover of Giant Steps somehow landed on my laptop.2

Quick, give it a watch and a listen. She layers lyrics she wrote over the song’s melody and then onto Coltrane’s initial solo.

I find this fun. Really fun. It’s not important to me whether the cover is actually “good” in a critical sense. Instead, this joyful performance re-presents the song as something fresh and new which is enough for me. It made me start listening to Giant Steps again.

And again.

And, good God, it’s a monster of a song. (YouTube | Spotify) Which I’ve known, and have always known, even though my ears detuned and stopped listening.

An anodyne conclusion to be sure but sometimes that’s where we end up in the journey from there to here. Area man likes song again after hearing a somewhat gimmicky cover.

This happens to me a lot though.

Ladies and Gentlemen, Some Covers

On Spotify I keep a covers playlist that’s resurrected songs I’d given up on. It’s also introduced me to songs I never gave a chance in the first place. Some current favorites: a bluegrass version of Queen’s Under Pressure and a neugrass version of the Smashing Pumpkins’ 1979.

(Songs mentioned from here on out are linked to on Spotify and YouTube down below.)

I like covers. They help me hear things I haven’t heard before. Or, I should say, I like covers that reimagine the original. At the extreme this includes musicians owning the original by completely reworking them. Think Jimi Hendrix’s version of Bob Dylan’s All Along the Watchtower, Joe Cocker’s take on The Beatles’ With a Little Help From My Friends, The Scissor Sisters’ disco rendition of Pink Floyd’s Comfortably Numb or Devo’s jagged and jangly cover of The Rolling Stones’ Satisfaction.

Less extreme is a modulation of the original. Perhaps the song is slowed down (M. Ward with David Bowie’s Let’s Dance), the instrumentation is modified (The Jolly Boys with The Rolling Stones’ You Can’t Always Get What You Want) or the vocal is drastically different than on the original (Annie Lennox with Neil Young’s Don’t Let it Bring You Down).

If you’re feeling sentimental, listen to Sleeping at Last bringing The Proclaimers’ I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles) to a heart-tugging crawl.

Cassandra Wilson is a personal favorite when it comes to covers. She both owns and modulates. Take a listen to her versions of The Monkees’ (!) Last Train to Clarksville or Cyndi Lauper’s Time After Time. Her covers are gorgeous.

Genre shifting is fun too. Reggae artists have covered rock and pop for years. See Little Roy’s cover of Nirvana’s Come As You Are, Peter Tosh’s take on Chuck Berry’s Johnny B Goode, Toots and the Maytals version of Richard Berry’s Louie Louie.

Some contemporary jazz musicians are crossing genres and doing covers well. The Bad Plus twists pop and rock songs into jazz pretzels. The result are sonically challenging and delightful whether they’re covering Nirvana, Tears for Fears or Black Sabbath. Brad Mehldau does the same. Here’s his version of Radiohead’s Paranoid Android. (Spotify | YouTube… you’re welcome).

“Elvis was a hero to most but he never meant shit to me” – Chuck D

Absent here is the long racial and racist history of covers; of white appropriation and “taking” of black originals; of black artists having to cover white artists in an attempt to “cross over” and get played on white-owned radio stations.3 Good entry points to that important, unfortunate history include How Rock and Roll Became White, by Jack Hamilton, and The Truth About Elvis and the History of Racism in Rock, by Stereo Williams.

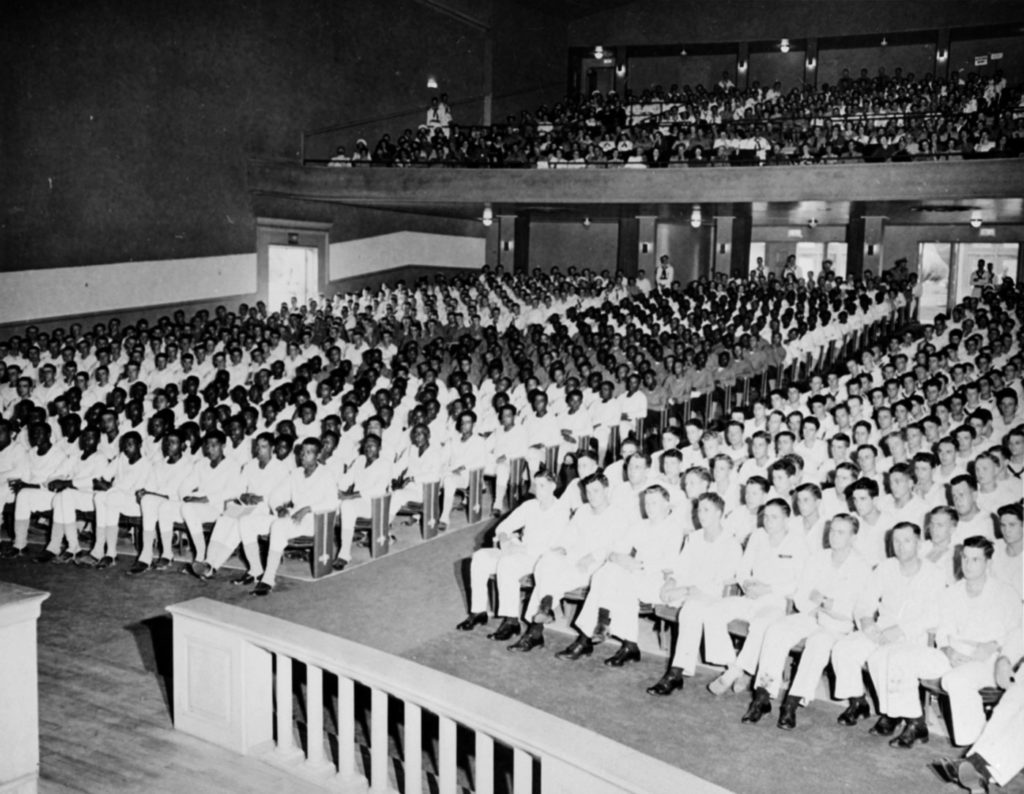

See also, Steve Knopper’s brief history of Jim Crow era concerts. It begins like so:

One night in the late 1950s, the Flamingos’ bus pulled up to a concert hall in Birmingham, Alabama, and a row of 30 to 50 police officers holding rifles and billy clubs was waiting for them. The cops escorted the six-member doo-wop group, famous for “I Only Have Eyes for You” and “The Ladder of Love,” to its dressing room and gave strict instructions: As black performers, they were to make eye contact with only the black fans, who were confined to the balcony, and not with whites on the floor.

“It was ridiculous,” recalls Terry Johnson, now 78, a member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame–inducted group. “The cops were up there making sure we did not look at any white person. It was a rule when we came in: ‘I don’t want to see any of you darkies looking at the white women out there. If you do, your ass is mine.’ Cruel things like that.”

Back To The Top

The cover is a rabbit hole. Listen to a good one and it makes you ponder the song – and music – more closely.

What is it that makes Giant Steps so monumental? Coltrane’s power? Sure. His dexterity? Definitely. The cadence of the melody before Coltrane takes off with his first dizzying solo? Yes, again. The Art Taylor/Paul Chambers rhythm section propelling everything along? Absolutely.

But music is ephemeral. Try to pin it down and it wisps away. It’s the individual parts and the collective whole. It’s the vibe. Again, like above, a somewhat anodyne conclusion. Then again, area man rediscovers love of song again after hearing a somewhat gimmicky cover.

Songs Mentioned

Here are the songs I reference above. If you use Spotify, my ongoing covers playlist is here.

- Cornbread Red, Under Pressure. (Spotify | YouTube)

- Darlingside, 1979. (Spotify | YouTube)

- Jimi Hendrix, All Along the Watchtower. (Spotify | YouTube)

- Joe Cocker, With a Little Help From My Friends. (Spotify | YouTube)

- The Scissor Sisters, Comfortably Numb. (Spotify | YouTube)

- Devo, Satisfaction. (Spotify | YouTube)

- Annie Lennox, Don’t Let it Bring You Down. (Spotify | YouTube)

- M. Ward, Let’s Dance. (Spotify | YouTube)

- The Jolly Boys, You Can’t Always Get What You Want. (Spotify | YouTube)

- Sleeping at Last, I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles). (Spotify | YouTube)

- Cassandra Wilson, Last Train to Clarksville. (Spotify | YouTube)

- Cassandra Wilson, Time After Time. (Spotify | YouTube)

- Little Roy, Come As You Are. (Spotify | YouTube)

- Peter Tosh, Johnny B Goode. (Spotify | YouTube)

- Toots and the Maytals, Louie Louie. (Spotify | YouTube)

- I think all art has a natural half life. For whatever reason, the work becomes so enmeshed in the ambient culture that it becomes somewhat of a token. Think Warhol’s soup cans, Led Zepplin’s Stairway to Heaven or Grandmaster Flash’s White Lines. back

- Vocalese is a singing style where were the vocalist sings words over the melodies originally performed by an instrumentalist.

In this case, Bertault wrote the lyrics to match up note of note with John Coltrane’s original solo. back - Easy example from above: while Toots and the Maytals cover Richard Berry’s Louie Louie it’s the all white Kingsmen who are typically associated with the song. back